Reading the text of a Shakespeare play and watching a film interpretation of it are very different experiences. Accordingly, annotation practices will then differ greatly as well. This post will reflect on my notes accumulated over the last few weeks from both reading play-text and watching film.

The most obvious difference that stands out when comparing my notes is that they focus on different elements. My annotations in the text centre on the structural, semantic and linguistic elements of the passages, whereas my annotations on film, record and examine the visual elements and rhetoric of film.

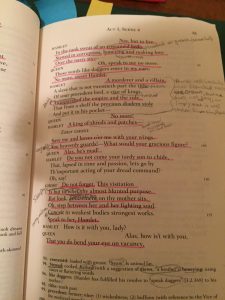

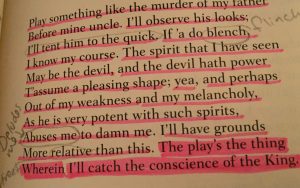

I always annotate the text in the margins and in between the lines, or anywhere I have room on the page, basically. I will scribble all around it, writing definitions, paraphrasing ideas, marking important elements, etc. I use a highlighter, pen, and pencil to underline, circle, draw arrows and stars, and generally make it completely undecipherable to anyone but myself. A few (of my most legible) examples are included below:

There is a craft to this madness, however, if it serves the purpose of helping me discern meaning in the language and verbal images of the text.

A major element in understanding text is attributing the correct historical definitions to Shakespeare’s words in order to make sense of the meanings. I use the Oxford English Dictionary and the editor’s notes for definitions and explanations on the many historical and cultural allusions in the text. I annotate brief definitions in the margins as I go.

I read the text generally, broken down into passages and closely focus on word choice, visual metaphors, puns and double meanings. I especially mark repetition of words and changes in rhyming pattern (Such as couplets emerging from blank verse to close scenes or speeches, very prevalent in Hamlet.)

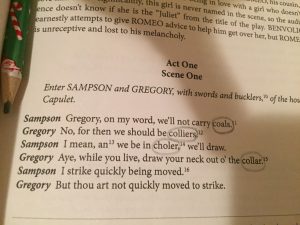

I am more attuned to catching puns when reading the text and annotate them. Shakespeare so often plays on the double meaning of words. A witty alliterative play on words is used to start Romeo&Juliet Act 1 Scene1:

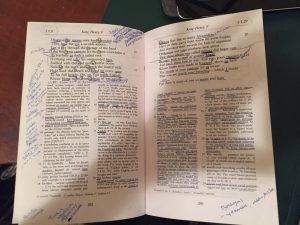

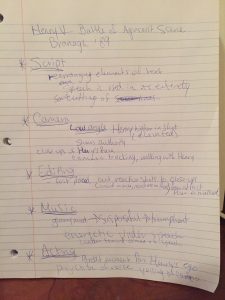

In contrast, my film notes focus on my observations of the cinematic conventions used. My notes on film comment on the editing style, the camera movements and shots, as well as the director’s creative choices like setting, landscape, casting, costumes, sound, and atmosphere. In preparing to watch and analyze a film, I’ve made it a habit to split my page into 6 headings to separate the elements of filmmaking: Script, Camera, Editing, Direction, Music, and Acting. As I watch, I can then keep my random comments organized by jotting details down into the corresponding category. One such example is my notes recorded while watching a scene from Henry V:

I find it very productive to cluster my notes in this way, not only to break down the film into its essential elements, but also to focus my attention on each of these components, to ensure I haven’t missed important points. I may watch the same scene four or five times, each time focusing on just one or two individual elements of the six. For example music is one that I particularly like to single out. I watch a given scene, ignoring all other elements to focus on the musical score. Modern cinema audiences are so accustomed to film score that we have been conditioned not to consciously pay attention to it. It’s a convention that’s designed to subconsciously invoke and manipulate emotion in the viewer. Focusing a section of notes on the soundtrack helps to distinguish the interpretive approach of the film.

As well, upon reviewing my film notes, I find far fewer observations relating to the word choice and linguistic elements of the script than in my text annotations. While reading text, I am continually defining and looking up individual words and phrases. However, while watching film, I mostly skip over unknown or unfamiliar words, as the general idea of the dialogue is more obvious from the visual clues. I also try to go once through the entire film following along in the text, to identify what has been changed (ie. lines, speeches, or scenes that have been re-arranged or cut out) in the adapting of the play-script into the screenplay.

The intended outcome of either form of annotation is to better comprehend, make sense of, and analyze the content in its respective medium.

I gauge the success of my text annotation practices by the extent to which I feel comfortable with the text and my handle on the dialogue and action in it. My particular annotation practices have served their purpose well and been worthwhile IF : I have reached a level of understanding and fluency with the text that feels as if I was reading it in modern- day English; I can construct vivid images of the action and characters in my mind as I’m reading; I perceive the plot coherently as a whole and am able to make solid connections between various scenes; and I can move through it with fluency upon re-reading. In the case of film annotation, its value is determined much the same way. The notes are useful if they provide insight on the film’s interpretive approach on various levels, and evaluate the rich relationship between Shakespeare’s original text and its film version. Annotation will help explore the various layers and elements of the text and/or film, allowing for greater confidence in the making and supporting of arguments.

Andra Sutherland

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.