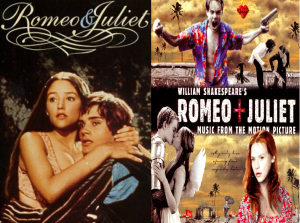

I have chosen to compare Act 2 Scene 1 of Romeo and Juliet (RJ) directed by Franco Zeffirelli (1968) and by Baz Luhrmann (1996). Zeffirelli’s version is more conservative, conventional, and true to the text. RJ 1996 on the other hand, is a modern adaptation of the same. While both films draw inspiration from the same text in terms of plot, dialogues and themes, their interpretation of the circumstances and the characters is varied.

The characters’ appearance in RJ 1968 is very authentic and historically-correct. The puffy gowns, veils and hairstyles sweep the audience into a different era, and are likely truer to what Shakespeare would have envisioned. Hussey (Juliet in this version) is a baby-faced, wide-eyed girl who looks very young. This is consistent with the 16th-century setting of the film where marriages occurred at a tender age. Danes (Juliet in RJ 1996), on the contrary, looks older and wiser in comparison. While still dressed appropriately for their roles, the costumes of the characters are significantly less elaborate and more modern—compatible with Lurhmann’s contemporary setting, enriched with technology such as cars, cameras, etc.

The lines, “What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot…” are a part of both versions of RJ. Hussey is hopeful and dreamy about renouncing their names to be together while Danes seems to reason with reality. She even gives the words “any other part/ Of a man,” a playful twist, hinting at male anatomy, which is more acceptable for her character and the time. In the text, Juliet talks to Romeo about coming across as easy: “…if thou think’st I am too quickly won,/ I’ll frown and be perverse and say thee nay…” These line are present in RJ 1968, and add to the portrayal of an innocent Juliet who does not want to play hard-to-get like other girls. On the contrary, saying such a thing would not be true to Lurhmann’s feistier Juliet and is hence omitted. This difference of character is also seen in the way both the Juliet’s report to their mother in the play—one is very obedient while the other’s tone suggests that she is the mistress of her own will.

While Zeffirelli’s RJ is more theatrical and dramatic, Lurhmann’s depict a more realistic version of young love. Romeo and Juliet (1968) come across as innocent, humble and flawless souls—almost verging on being surreal. Their 1996 versions however, are deliberately portrayed as immature teenagers. The line, “Therefore thy kinsmen are no let to me,” is said loudly by Romeo in both films. Leonard Whiting says it out of passionate love while DiCaprio’s interpretation of it is more rebellious. He stands taller and shouts into the distance, intending for “the kins” to hear his words, knowing full well, the dangers of being a Montague on Capulet property. A similar sense of carelessness is seen when DiCaprio climbs the walls and creates a lot of ruckus and noise as opposed to Whiting, whose entry and climbing are a lot quieter and controlled.

3:45-4:00 (Zeffirelli, 1968)

The intimacy between Romeo and Juliet is more physical and abundant in Lurhmann’s version. Low angle shots of Juliet being admired by Romeo from a distance are soon followed by Juliet coming down to the garden where Romeo sneaks up from behind her. The garden, lighting and pool add to the sensuality of the scene. The lack of sound maintains focus on the conversation while adding to the realism of the film. Romantic, harmonious music then plays and gradually gains intensity alongside the scene as the couple makes promises. Physical interaction between the lovers is limited in Zeffirelli’s RJ, and rightly so, in synchrony with the conservative atmosphere of the era. Their proximity is also physically limited by a thick balcony railing. The use of mid and eye-level camera angles in this film is basic and non-impactful. Romantic music plays in the beginning when Romeo admires Juliet secretly, stops when they are talking, and then resumes when they make promises. This use of classic dramatic music adds to the theatrical air of RJ 1968.

0:00-0:37 Lurhmann, 1996

In conclusion, both films are a tribute to Shakespeare, and prove yet again, that his plays can be film material after all. While both of these versions of RJ have their own place in cinema, I think that Lurhmann’s take on it is more unique and does a better job of drawing in the audience. The realistic modern-day interpretation of the same themes makes the film more relatable and impactful for me.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.